What is an Autism Assessment?

An autism assessment is a comprehensive evaluation of children’s behaviour and interactions to determine whether they may have autism. Since there is no single medical test that can diagnose autism, psychologists use a combination of interviews, observations, and standardised assessments to determine how a child’s behaviours and interactions compare with the varying characteristics of autism.

When is an Autism Assessment Recommended for a Child?

The signs of autism can become clear from an early age, but autism is typically diagnosed from 2 years of age. In some cases, the signs of autism may not be identified until a child starts school.

Early indicators that a child may have autism include:

- Delayed talking or not talking at all compared to typical developmental milestones

- Self-stimulating behaviours such as rocking, flapping hands, or pacing

- Developing strong special interests (e.g., only playing with trains)

- Strong sensory preferences (e.g., overwhelmed by loud noises or seeks out specific textures)

A psychologist specifically trained in administering autism assessments can evaluate your child’s communication and behaviour.

Benefits of an Autism Assessment

An autism assessment provides detailed information about your child’s communication, behaviour, sensory and learning preferences and can have many benefits for your child and family.

Some of the most common benefits include:

- A better understanding of your child’s unique interests, how they communicate, and what their behaviours mean

- Development of an individualised learning plan and access to support classes at school

- Identification of suitable classroom adjustments such as modifications to the environment, use of visuals, breaks in learning, and access to noise-cancelling headphones

- Eligibility for funding such as the NDIS and specialised support services

The Assessment Process

An autism assessment involves multiple steps and components to ensure a thorough evaluation. A psychologist may include:

- Developmental history, which may include questions about your child’s birth, when they started walking and talking, and if there are other family members with autism or other neurodevelopmental disorders

- Comprehensive standardised parent interview to understand your child’s development in three key areas – communication, social interaction, and distinct behaviours

- Play-based observation to see how your child interacts and plays with you and others, and identify any behaviours that may be characteristic of autism

- Standardised assessments, such as a cognitive assessment, to rule out other explanations for your child’s behaviours

Understanding Assessment Results

Following an autism assessment, the psychologist will provide you with a detailed report sharing the outcomes of the assessment.

The psychologist scores each behaviour based on how frequently it was observed throughout the assessment. In the report, this will be interpreted into descriptive comments such as “little to no signs of”, “some signs of”, or “significant signs of” followed by the behaviour, communication, or interaction being observed.

At the end of the report, the psychologist will include a comment that summarises their findings. This comment will state whether their observations are consistent with an autism diagnosis and to what extent. For example, “showed several signs in all areas that are consistent with an autism diagnosis” or “not displaying enough signs to be consistent with an autism diagnosis”.

If your child is diagnosed with autism after an assessment, they will also receive a classification of level 1, 2, or 3. This represents the level of support your child needs and is used by funding bodies such as the NDIS to help determine a support plan.

If a diagnosis is not made following the assessment, the report will still include recommendations about the next steps to take, whether this is further assessment, therapy, or strategies to try at home and at school.

Assessment Tools Used by Learning Links

Learning Links’ psychologists use two assessment tools to evaluate if a child may have autism:

- Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) – a comprehensive parent interview tool used to gather information about a child’s development.

- Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2) – an accredited play-based tool used to observe children’s play, communication, social interaction, and behaviours.

Take the Next Step: Book an Autism Assessment Today

If you suspect your child’s communication, behaviour, and social interaction may be characteristic of autism, our comprehensive assessments can provide clarity and guide you towards the next steps. Contact us today to book an autism assessment so you can find the right support for your child.

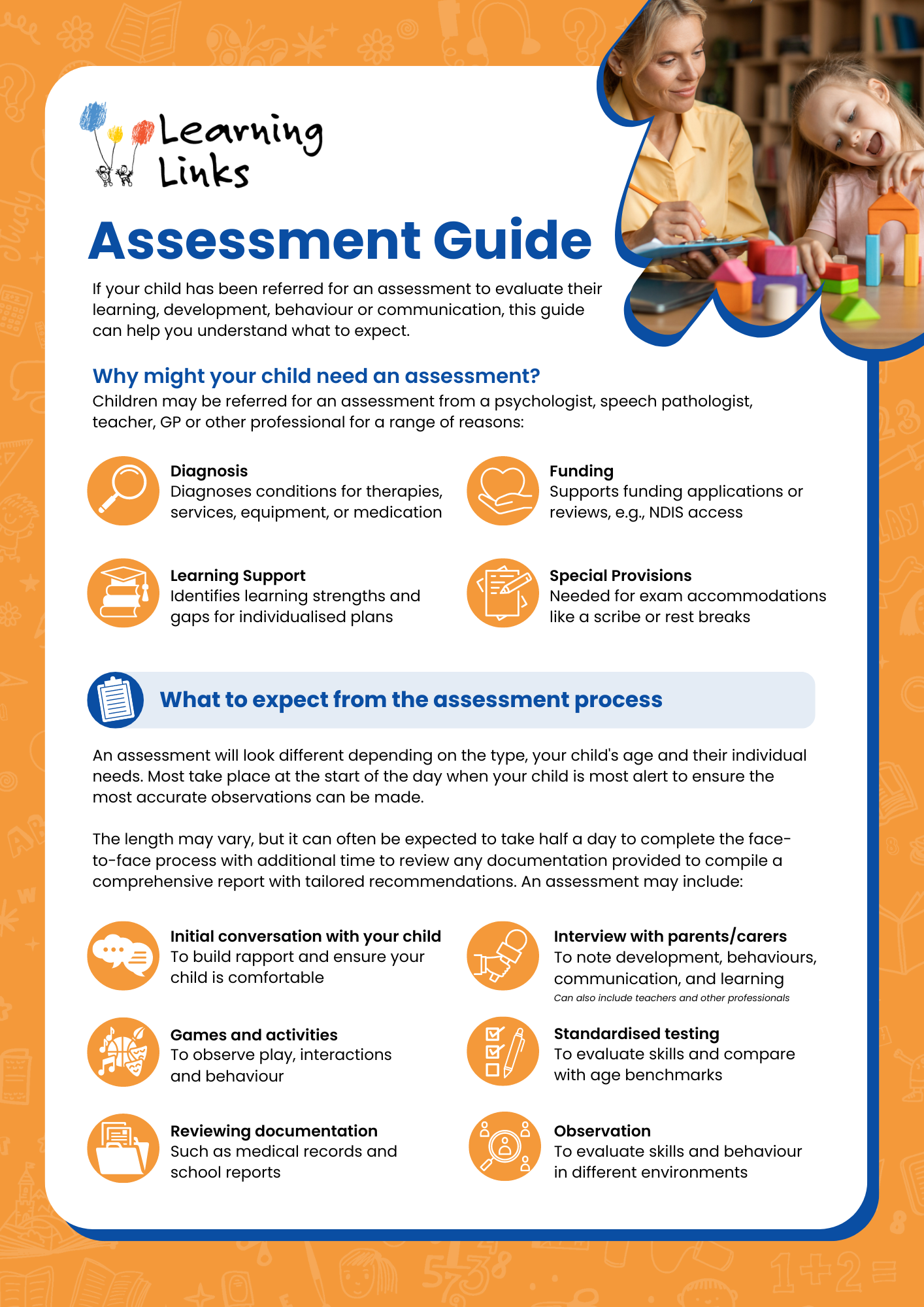

Download Our Free Assessment Guide

This assessment guide aims to demystify the evaluation process and introduce you to the wide range of psychological assessments available for families so you know what to expect and how to select the best option for your child.

Explore More Assessment Types

Other Learning Links Services

We work closely with children and families to truly understand your unique situation and offer personalised and evidence-based therapies to support positive change.

Find Out More About Psychology

We use fun and interactive strategies to meaningfully engage your child to build their speech, language and literacy skills, and the confidence to communicate and interact with others.

Find Out More About Speech Therapy

Our tutoring program is tailored to the individual needs and learning style of your child, so we can focus on filling the gaps in their learning to help them build skills, motivation and confidence.

Find Out More About Specialist Tutoring